Early Monday morning, the U20s kicked off their World Cup run with a dramatic 3-3 tie, leaning heavily on a 94th minute volley from Luca de la Torre. Despite the late game heroics, many pointed to Jonathan Klinsmann as the weak link of the team after conceding three goals. (Read BigSoccer's game day thread to hear fans go from awe to disgust in a matter of seconds.) There are many fans calling for Klinsmann's benching, while some seem to have been harboring their displeasure with the goalkeeper for some time.

Let's take a closer look at his performance before we dive into who should be the starting goalkeeper.

First Goal

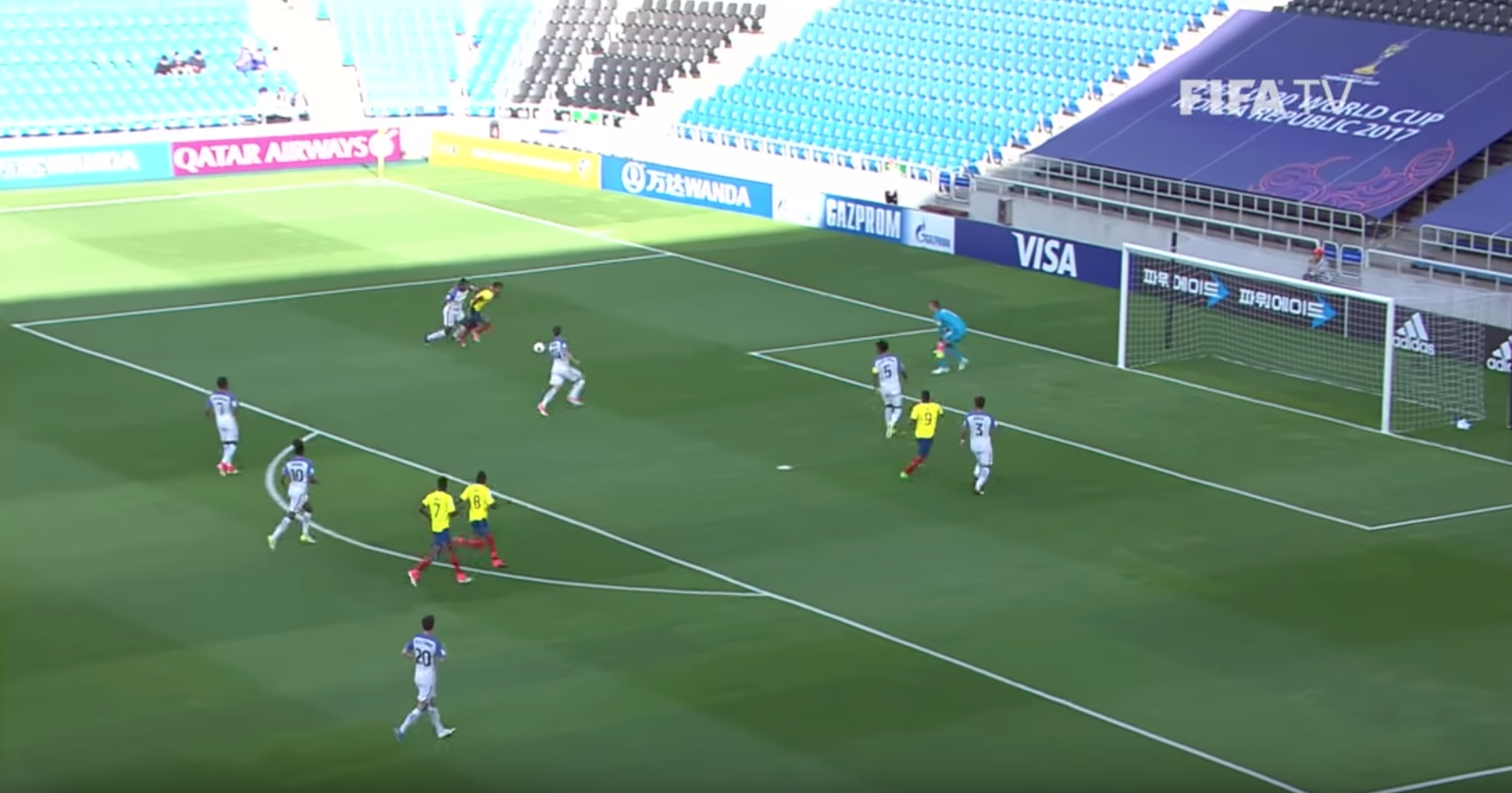

You know a situation is bad when your main defender is in the process of starting his first of two somersaults. It's a tricky situation for Klinsmann because if he stays home, maybe he should have gone and vice versa. In these situations, the decision comes second to the execution. There's a right and wrong way to attack and there's a right and wrong way to stay back. It's not realistic to expect goalkeepers to know how everything is going to play out on 1v1s. Ultimately, they must make a decision and execute it as best they can.

Klinsmann decides to step to the ball and his approach is originally thought out well. He steps to the striker (second picture) as a touch on the ball is made, which is the exact time a goalkeeper should step. The longest amount of time a striker has before touching the ball is right after his preceding touch. The longer a goalkeeper waits to step after a touch, the closer the striker is to his next touch.

Building off the earlier point, Klinsmann's final execution is lacking. He makes up his mind very early to throw out a studs up one-footed tackle for an attacker who is going across Klinsmann's body. If Klinsmann throws his hands out low to his left, there's a high probability he knocks the ball away.

Additionally, Klinsmann is asking for a red card here. When accessing a referee's call on a play, a goalkeeper must limit the possibility of what a referee could call against them. Klinsmann does not receive a card on the play (personally the correct call) but it's very easy to see how a referee would give a red card to Klinsmann. Perhaps the touch doesn't lead to an open teammate and the striker goes to ground. We've all seen referees award red cards for similar plays and Klinsmann doesn't protect himself with an exposed one-footed slide that gets close to a scissor tackle.

It's an undesirable situation, but Klinsmann doesn't help himself as much as he could. A hands-led tackle likely stops the first goal and keeps the scoreline level.

Second Goal

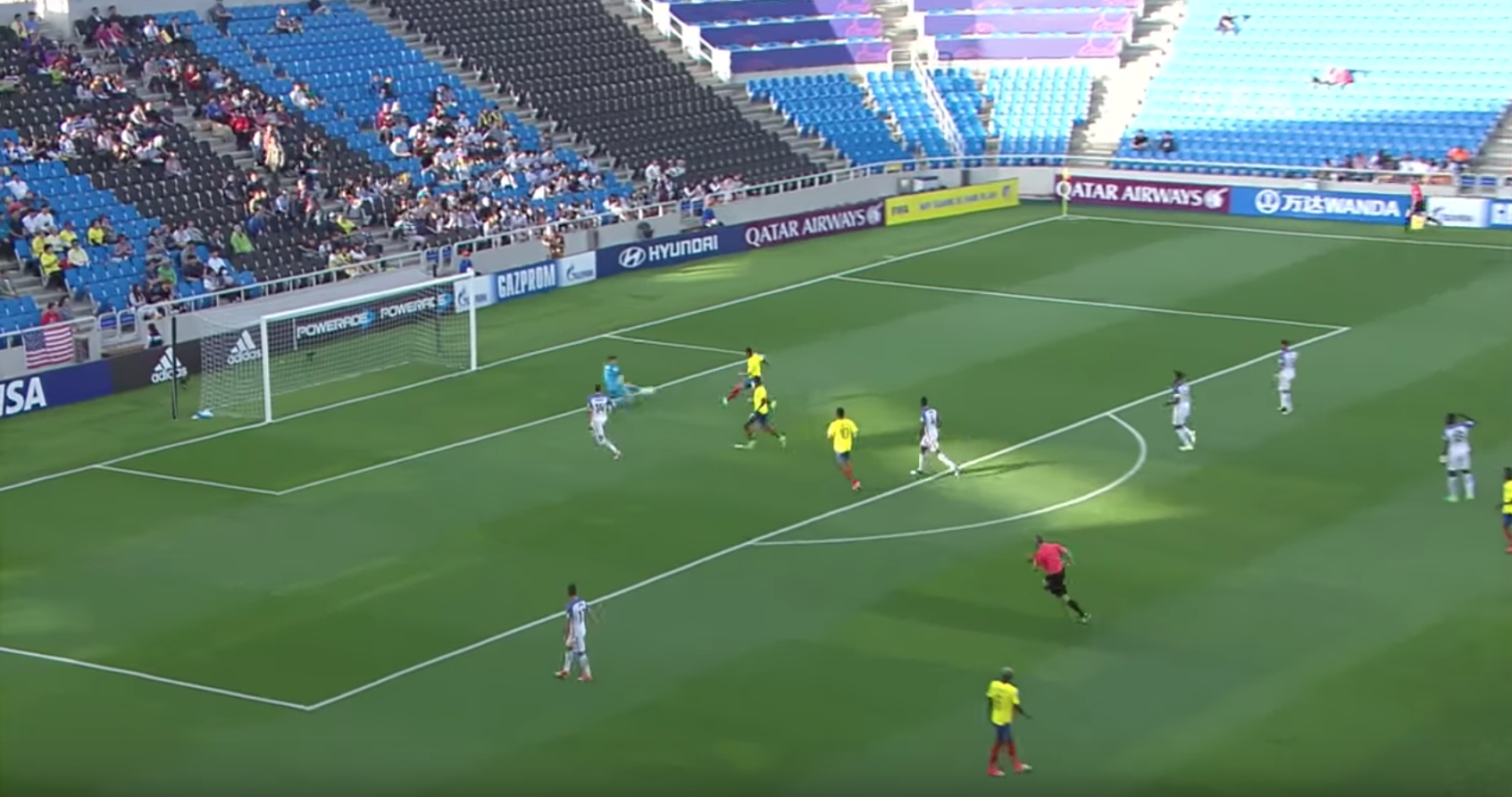

This is a great example of how 1v1 situations can be drastically different from one to the next. The Ecuadorian striker takes a long touch but because of the defender staying in the picture (despite ultimately losing out) Klinsmann doesn't have a clear road to attack the ball. If the defender were to have an opportunity to clear the ball but only receive a tackle from Klinsmann, the chaos could very well backfire on the American defense.

Klinsmann's decision to stay home isn't necessarily wrong, but his execution is problematic again. He creeps up on the play in order to be ready to pounce on an extra touch but inadvertently puts him in a version of "no man's land". He is too far forward to give himself time to react but not far enough forward to cut down the angle to any real value.

Even more concerning, Klinsmann's feet go cold at the exact wrong time. Notice in pictures 3-6 how slow he is to move. The ball is not struck far from his body (the bending shot hits close to the middle of the net) yet his feet's loss of movement stops him from moving his upper body in time.

His weight is also too far back. (Picture 4 looks like he's sitting in an invisible chair.) The only movement he can do is a hopeful leg thrown forward, which is entirely the wrong motion needed. His body falls backwards, into his weight.

I'd like to see Klinsmann stay a step back here to give himself more time to react but the bigger issue is his feet. If his heels rest on the play (aka "cold feet") he makes the play ten times harder on himself. His upper body can move quicker if his feet are ready to spring but he's cemented himself in place. For a shot not hit far away from his body, it's a play that a goalkeeper of Klinsmann's caliber should be able to do more on.

Breakaway Save

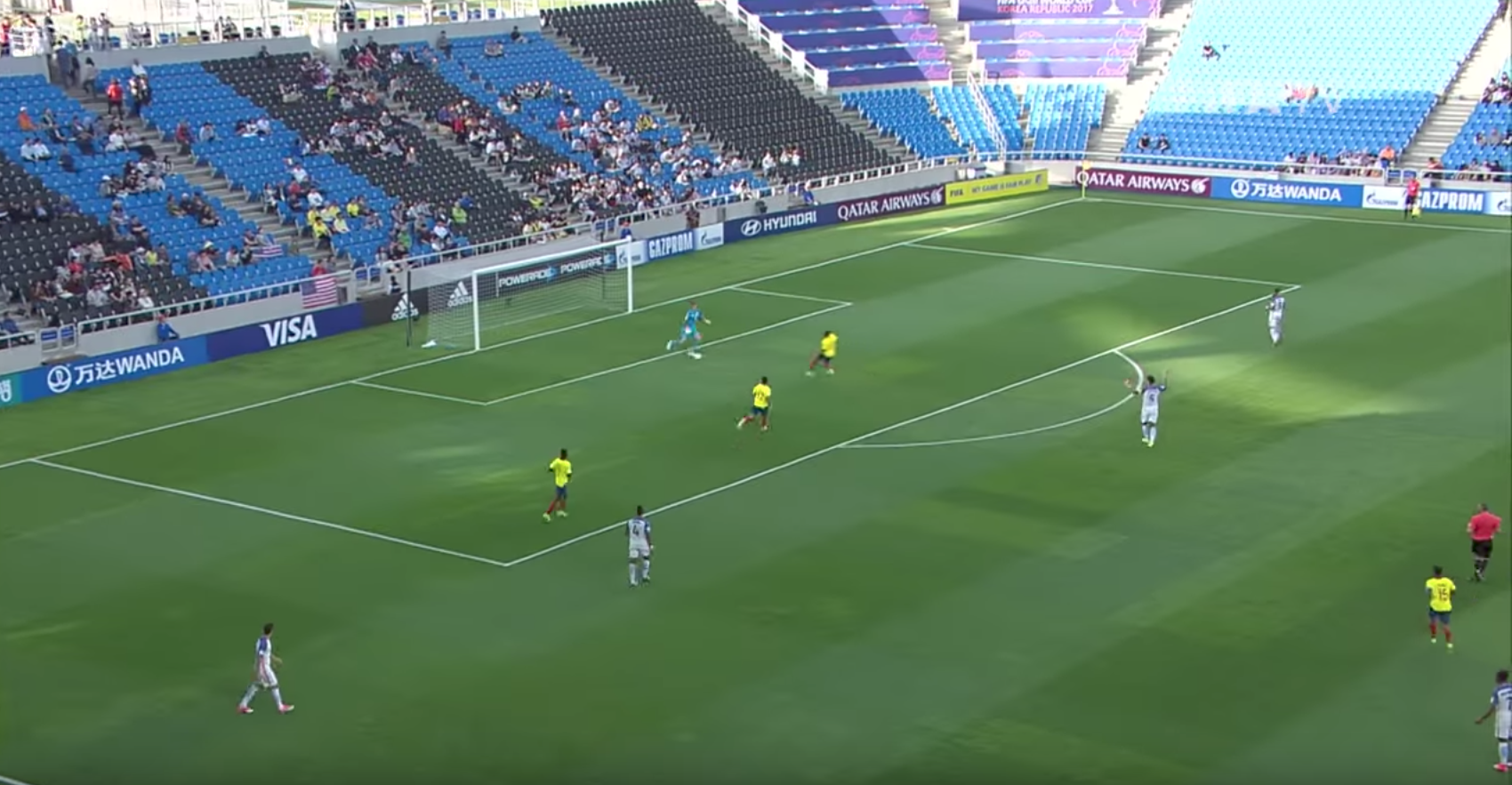

For a game that was 2-2 with only 30 minutes left in it, it's hard to be critical of any save. Klinsmann forces the shooter to a take a shot into his body and the US were let off the hook for bad defending. However there are some worrying signs on the play.

The offside trap fails, as always, because of one defender. Unfortunately Klinsmann gives no verbal warning of the sneaky striker and appears to have no idea he's even there. Notice how Klinsmann goes to collect a long through ball only to realize there is a perfectly timed striker heading towards goal. (Second picture, Klinsmann is correcting his wrong step with his right foot. The misstep is displayed better in video.)

It's a fine save, but Klinsmann needs to keep an eye on backside runs to limit chances on goal. A goalkeeper should look to be preventative when dealing with shots and only have to make the saves when previous attempts of communication have failed.

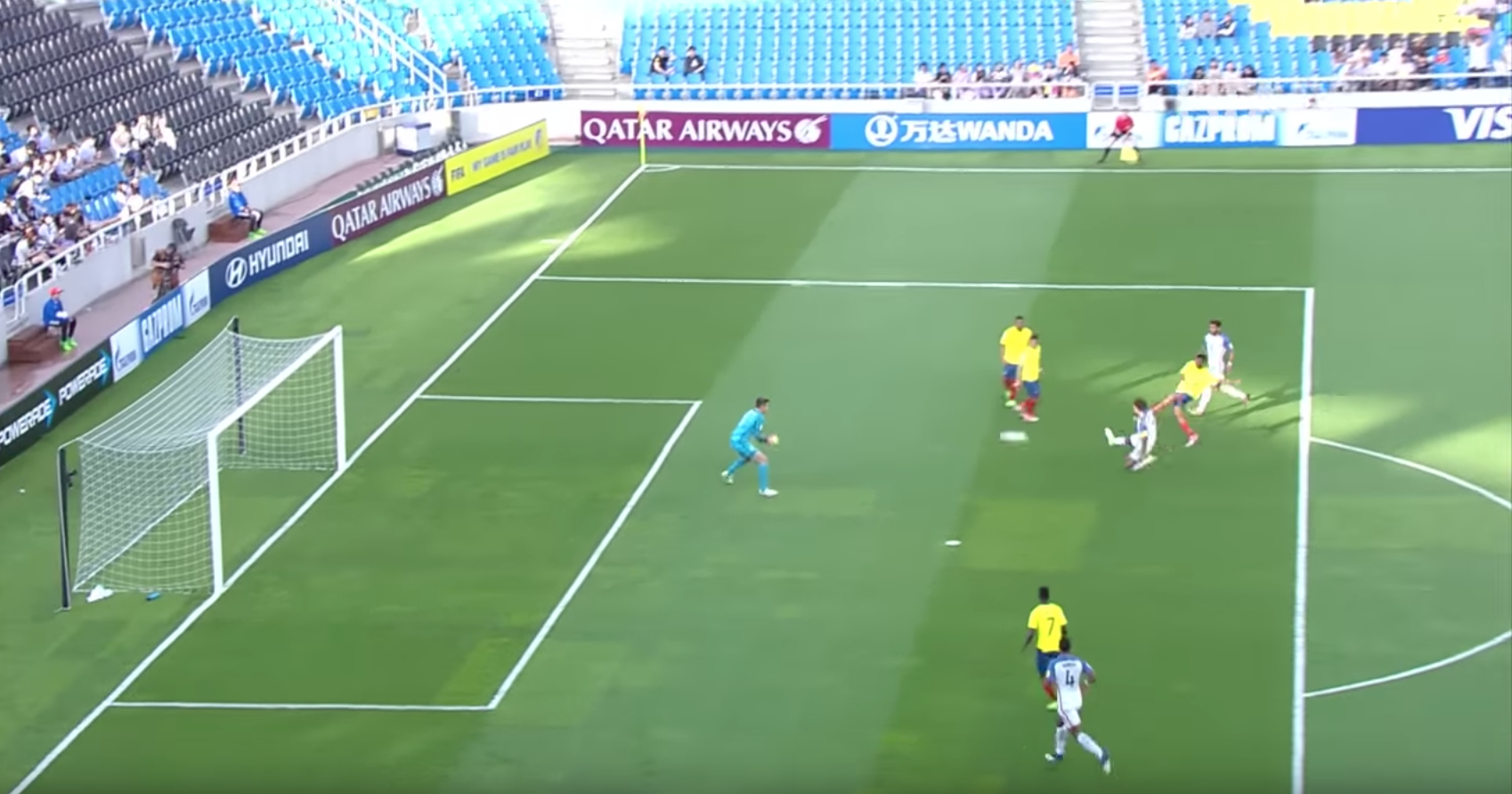

Third Goal

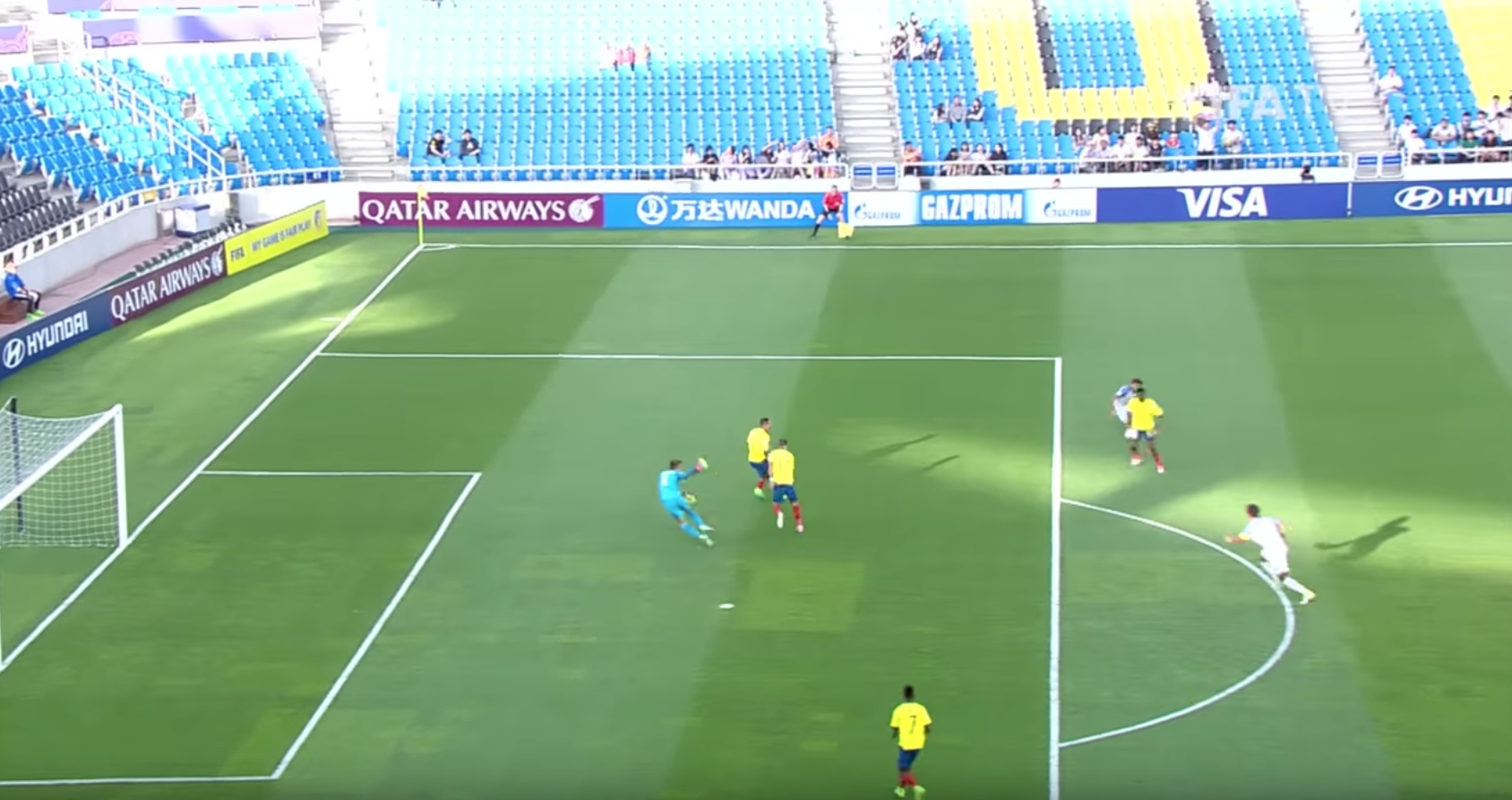

Finally we arrive at Klinsmann's worst mistake. Needless to say it's a mistake that Klinsmann will be criticized for some time and honestly there is no protection for Klinsmann here. Some may argue that he shouldn't receive the back pass or that his left back should have opened up more for him, but the error is solely on Klinsmann. Players constantly receive undesirable situations but their redemption is rooted in if they made the best with what they could. Klinsmann, in contrast, makes a bad situation even worse three times over.

First, Klinsmann's starting touch is across his body with right foot (second picture). The awkward trap loses time for Klinsmann and sends out a loud alarm to defending attackers that the goalkeeper can't play with his left foot. A confident left footed trap dissolves the situation, despite little help from his teammates.

Klinsmann's second mistake is found in his following touch. Recognizing that he has no realistic options and is surrounded by yellow shirts, he must place the ball into the stands. Even if this results in a corner kick for Ecuador, at the very least the US could set up to protect the goal. Instead, Klinsmann tries to take another touch to round the first defender to little success.

Lastly, after Klinsmann has gifted the ball back into the opposition's possession, he panics in retreating to the goal. There is no time for Klinsmann to achieve better positioning. He must stand his ground and do what he can from there. The seven or eight backwards steps transform Klinsmann into the equivalent of a traffic cone. The shot is not struck far from Klinsmann (see last pictures) and if he does not backpedal, or at least limits the number of steps he takes, he can likely make the save.

Perhaps the most frustrating part, Klinsmann looks completely defeated after the goal. His teammates already know he has messed up - everyone in the stadium knows in - there is no need to confirm a sense of disappointment in the play. There will be plenty of time to feel sorry about the mistake after the game. In the middle of turmoil, a team needs their goalkeeper to get them back on track, not mope alongside them.

Who Should Start for the U20s?

In true USYNT-form, we're left with one seasoned goalkeeper and a handful of untested backups. JT Marcinkowski has seen one game with the U20s in a throw away match, so it's hard to say how he would perform. For those who have watched him at Georgetown, he's performed very well but it's not necessarily a 1-to-1 transition to the U20s.

Ultimately there is a lot of information fans don't have. How does the player chemistry differ from Klinsmann to Marcinkowski? How did Klinsmann respond to the team after the game? In the next practice? Was the US's third goal a rally from the team's respect for Klinsmann? Has Marcinkowski put himself in a position with the team to confidently take over the starting spot? What do the coaches know about the goalkeepers that we don't? There are several questions we just don't have the answers for.

There's a strong possibility Klinsmann will be benched for the second game, but calling for it is admittedly based off a slice of information. Perhaps the bigger problem is that Marcinkowski hasn't had the opportunity to show his value. If we're worried that Klinsmann won't give his teammates confidence in the back, Marcinkowski's lack of game time doesn't solve that problem.