For several decades, the starting goalkeeper for the US national team possessed a supernatural aura that convinced fans the US would always have a chance at a result, no matter how difficult the opponent was. From Borghi to Scurry to Howard, each goalkeeper provided iconic moments that now live on as some of the greatest performances by an American goalkeeper. However, the two national teams’ goalkeeping pools have diverged significantly in recent years. Whereas the USMNT’s goalkeepers have clearly failed to uphold their reputation as English Premier League-level talent, there’s some debate on whether the USWNT’s goalkeepers are still in the conversation for best in the world. So has the USWNT managed to avoid the USMNT’s woes? Or has the USWNT learned nothing from the USMNT’s problems?

How the USMNT Got Here

There are many factors that go into a country’s goalkeeping pipeline and the USMNT has unfortunately struggled to continue to execute on most of them in the 21st century. After the USSF decided to not replace Peter Mellor as the federation’s goalkeeping director in 2005 and continue on without anyone overseeing the goalkeeping department, the federation’s goalkeeping education decayed so badly that in 2015, they pulled it off the shelf. Although the USC would continue with its grassroots goalkeeping courses during this time, the federation would also pull back any serious goalkeeping focus on the common letter licenses (A, B, C, etc.) for aspiring head coaches.

On top of the removal of goalkeeping education, the distilling of traditional pathways like ODP in favor of MLS academies ended up outsourcing the position’s development to a handful of turbulent places, instead of being led by a clear governing body. MLS’s goalkeeper coaches arrived and left every 3-5 years, continually bringing new ideas and discarding old philosophies, making the American goalkeeping pipeline akin to a truck spinning its wheels in mud.

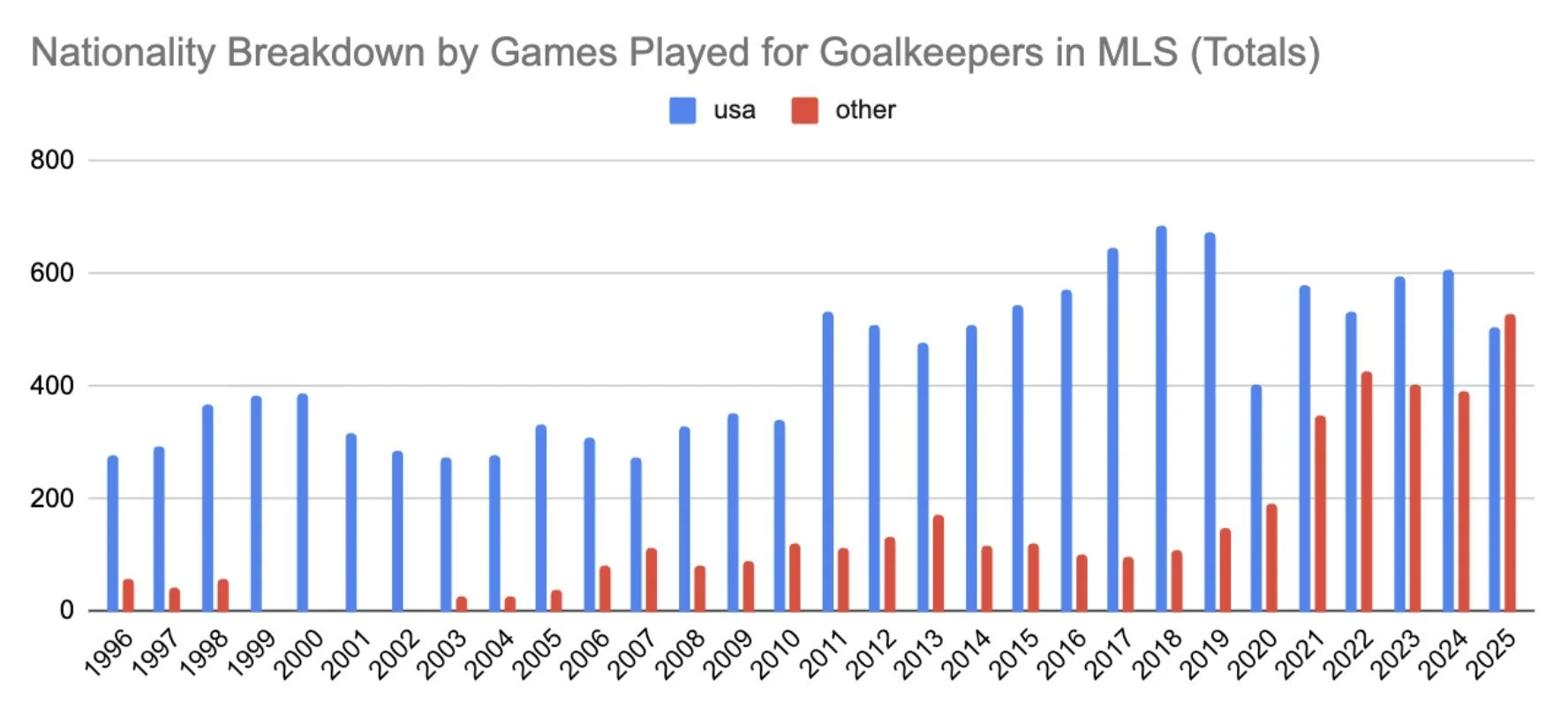

In an attempt to bolster the newly minted league, MLS Next started pulling in more clubs with the promise that the non-MLS-affiliated sides would receive solidarity payments, but only if they joined MLS Next. These efforts put young, talented goalkeepers in a bind, leaving them with essentially the choice of finding an MLS Next team in order to receive any investment from the federation or being left out in the cold. Fast-forward to 2025 and this half-baked effort led to a league that rarely produces American goalkeeping talent and plays more foreign than domestic goalkeepers, while the country faces a unique problem of a goalkeeping logjam where goalkeepers’ professional pathways get choked out, stifling their development at a crucial stage.

In 2025, MLS featured more foreign goalkeepers than American for the first time in the league’s history.

But what’s to say about the women’s setup? Four former professional goalkeepers from the women’s game weighed in on the current USMNT/USWNT goalkeeping situation: Saskia Webber (Rutgers, USWNT), Jill Loyden (Villanova, USWNT), Michele Dalton (Wisconsin, Chicago Red Stars), and Emily Armstrong (UConn, IBV).

Are the USWNT Avoiding the USMNT’s Potholes?

For most of its existence, the women have largely been forced to carve their own path as the federation would not treat the two national teams equally. As former NT goalkeeper Janine Szpara explained it, “US Soccer has a pattern of not supporting and giving the women what they need or what they deserve.” Even in more recent years, we’ve still seen an imbalance in investment. In 2018, when the USSF tried to kickstart a new goalkeeping license, it was MLS coaches, not NWSL coaches, who were invited to the pilot course.

So left adrift from the federation, the main saving grace for the women’s goalkeeping pipeline was that the US had the elite youth system in the entire world for the last 50 years, and, whenever afloat, a top professional league as well. The US enjoyed an early advantage in goalkeeping due to these investments. Emily Armstrong, who finished her career with UConn in 2016, spoke on her difficulty in going from the US to Europe when it came to what she expected to receive.

“While training with the Thorns and the Spirit, I had access to goalkeeper training on a daily basis, and even had opportunities for additional training outside of the daily practices. This was not the case overseas. In some situations, there was no goalkeeper-specific training offered, and I had to advocate for myself. At the time I was a little frustrated by this fact, but looking back on my experience, I am thankful that I was put into situations where I had to speak up, and find ways to improve my game without the routine goalkeeper training I was used to at UConn and in the NWSL. In Norway, I would train with the men’s keepers, because the women’s team did not have a goalkeeper coach of their own.”

But as the US gained a significant and early lead, with early stalwarts of Brianna Scurry and Hope Solo shining brightly on the world stage, these advantages started to erode. What Armstrong faced just ten years ago is now largely referred to as “back then” or a time that’s not really relevant to top European clubs. The US, in turn, didn’t do much.

“We haven’t put resources into education,” states Loyden. “Our goalkeeper coaches thought, ‘Oh, it’s a technical position.’ Coaches became overly technical and killed athleticism. Then the game evolved for goalkeepers to use their feet and we were even further behind.”

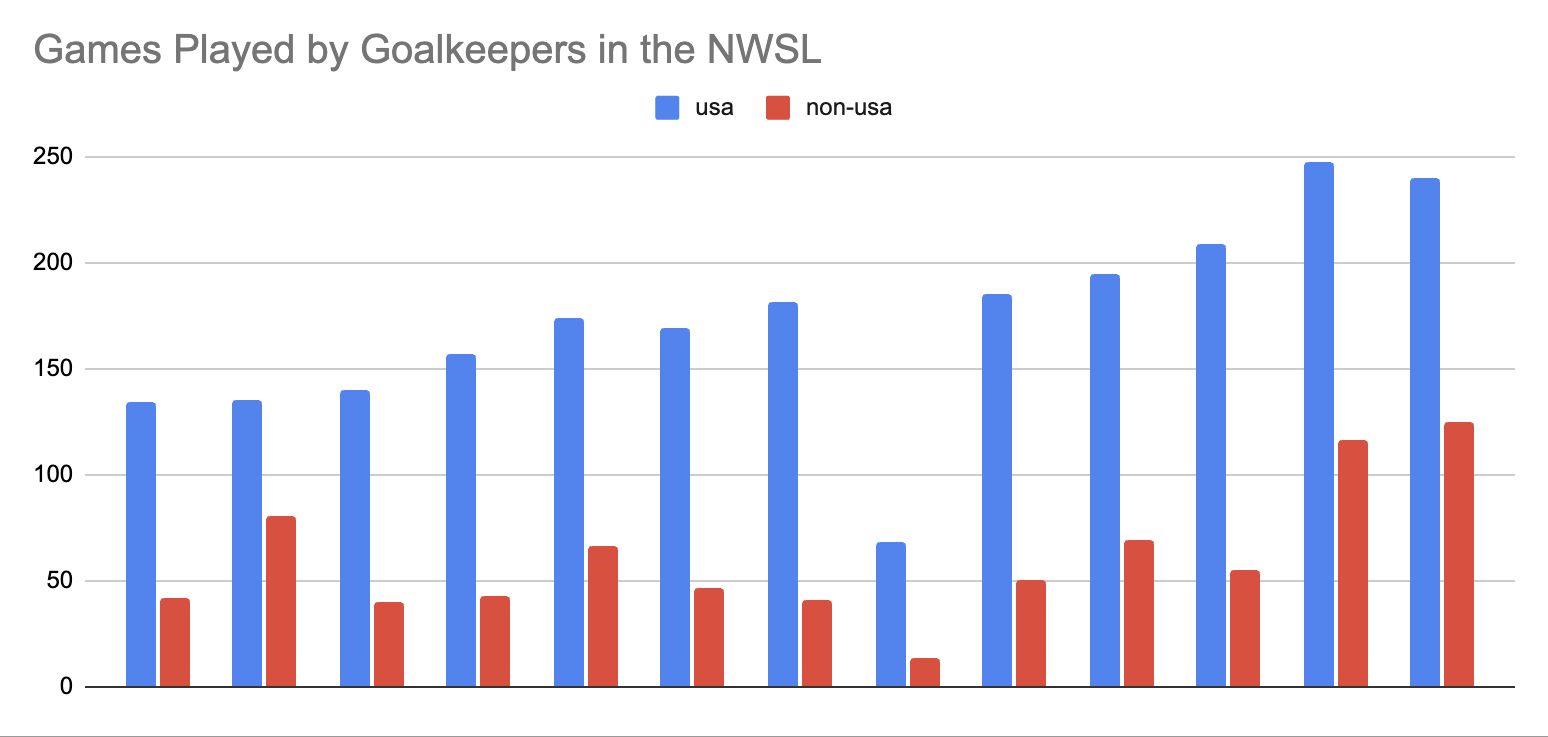

Exiting 2025, the NWSL’s top goalkeeper has now come from outside the US three out of the last four years and they’re starting to see a similar trend line that MLS faced just five years ago: games for Americans are going down while games for international goalkeepers are at an all-time high.

So while the US was once reaping the rewards of having the top league in the world filled with American goalkeepers, NWSL coaches are looking more and more overseas to find goalkeepers who are well-rounded out, having less trust in the underdeveloped American goalkeepers. Webber and Dalton express concern about the next steps for the USWNT when trying to replace Naeher.

“I don’t know if I would say [the USWNT] are having an easier time [than the men],” writes Webber, “None of the goalkeepers in the [USWNT] pool right now have enough experience or have proven themselves in a major tournament to grab the number one spot.”

“I actually don’t think the USWNT is having an easy time replacing Naeher,” echoes Dalton. “I do think Naeher replaced Solo pretty seamlessly. The men seem to always be behind the rest of the world, and instead of closing that gap, we continue to further ourselves. On the women’s side, more resources are becoming available to women internationally, so other countries have been able to close the gap.”

Substance Over Style

Continuing to invest in American goalkeeping poses a difficult question. “What exactly is American goalkeeping? What does it look like? How does one define it?” These questions are difficult to answer largely because it’s hard to find a consistent thread from the top. From Friedel to Howard to Freese, the USMNT has started three very different goalkeepers in a relatively short time. From Scurry to Solo to Naeher, again, three very different goalkeepers wore the number one shirt for the national team. And while the lack of a specific identity may not be met with a consensus, all four retired goalkeepers speak about the importance of a clear blueprint to uplift American goalkeeping, even if it is just a detailed approach for one specific individual.

“What is our identity?” asks Loyden. “I don’t know what that is. But I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing. We teach the ABCs at The Keeper Institute. Adaptable, brave, and consistent problem solvers. But consistent problem solvers can do that in a variety of ways.”

Loyden’s modern approach works well for goalkeeper coaches, as one team may have three vastly different skillsets that the coach must now work with collectively. And for the goalkeepers themselves, the intangible focus of the ABCs is a breath of fresh air, allowing the individual to figure out what works best for them, as opposed to shoehorning a calloused approach.

“I had goalkeeper coaches who worked with my style of play and made adaptations as needed,” said Armstrong. “I also had goalkeeper coaches who tried to change my style to fit theirs. I believe there is always room for growth, but I also think it’s important to meet the goalkeeper where they are, and progress from there. Every keeper has their own style, and there really is no ‘correct’ approach to the position. The goalkeeper coaches I appreciated most were those who would break down film and give me pointers, plus also listen to my perspective. I had the most growth with goalkeeper coaches who I could discuss both positive and negative plays in the game.”

Both Armstrong and Dalton now work with the next generation of goalkeepers and they haven’t forgotten what did and didn’t work for them in their playing careers. The intangible lessons learn are a signficiant compass in how their now coaching young, aspiring goalkeepers.

“An individual’s ability to take in new information while staying true to themselves is pretty paramount in being successful. I’m a big believer that instilling confidence and belief in a goalkeeper has to come above style. Maintaining consistent principles is key when styles vary,” says Dalton.

Tracking all the way back through playing in WUSA, Japan, and at Rutgers, Webber recognizes the problem young goalkeepers today face when they’re pulled in too many different directions. “The funny thing is all my coaches [across my career] had the same basic philosophies around the position and training. Possibly because they had all worked together. The problem today is that doesn’t happen as much, so young goalkeepers can be all over the place when they move from team to team or coach to coach.”

Optimistic Future

As we enter the next quarter of the century, our retired goalkeepers are still making positive impacts on the game, whether it is by becoming a goalkeeper coach themselves or offering insightful goalkeeping-specific commentary on nationally televised broadcasts. These efforts go a long way but the need for a federation-coordinated effort is still paramount. In Fall 2024, Jack Robinson was hired as Head of Goalkeeping after a nearly two-decade run through the highest ranks in England. Recently, Robinson talked about his efforts with the federation to help goalkeeping in our country, highlighting an expansion in goalkeeping education, more talent identification across the country, and the benefit of national team managers who want to utilize their goalkeepers as something more than a line sitter. These are encouraging signs, but for the last twenty years, American fans have been waiting on the federation to fulfill its promise that goalkeeping investment was on the way.

As of right now, the USWNT are still able to boast about having one of the top goalkeepers in the world between the posts. So things aren’t currently as dire for the women as they are for the men. However, when looking back to where the USMNT was with their 2002 and 2006 World Cup rosters - featuring Brad Friedel, Tim Howard, Kasey Keller, Tony Meola, and Marcus Hahnemann - Ernest Hemingway’s quote comes to mind. “How do you go bankrupt? Two ways, gradually. Then suddenly.”

Can the USWNT avoid the USMNT’s pitfalls? Time will tell. If we embrace the country’s strengths and continue ramping up investment into the position, the ceiling will skyrocket. On the other hand, unkept promises will only put the US further behind with its goalkeeping for not just the men, but the women as well.

“I don’t believe there’s one way to play the position,” Loyden says. “You can interpret it in so many ways. The more adaptable you are, the more solutions you have. If we’re not preparing goalkeepers for the demands of ten years from now, that’s a problem. We won’t know what they will look like [in ten years], but if we develop them to be adaptable goalkeepers, they’ll be able to play in that modern game.”